Idaho- A State Where Time Is Optional

In most jurisdictions, dates matter. Doctors timestamp prescriptions, bankers date checks, and notaries write the day they saw you sign. In Idaho, apparently, dates are mere decorations—like parsley on the edge of a plate.

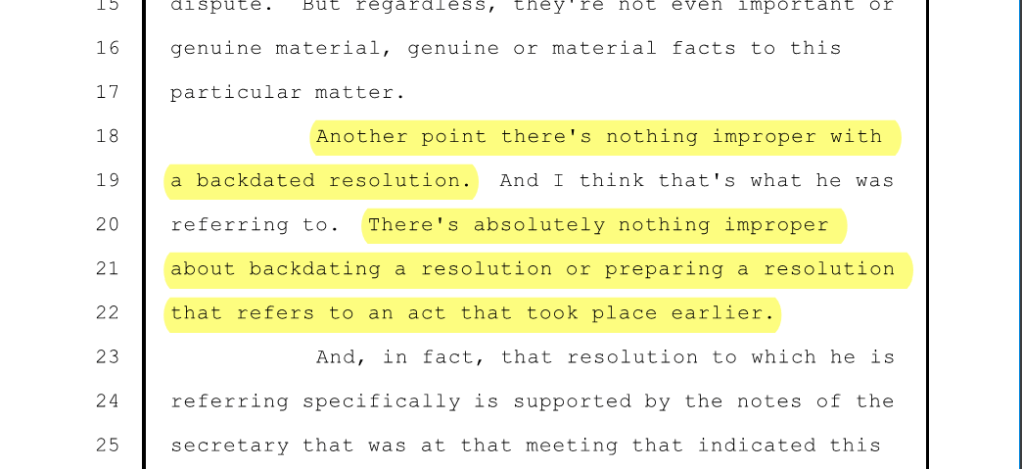

When defense attorney Mr. DeFord declared in open court, as preserved in the official transcript,

“Another point: there’s nothing improper with a backdated resolution… There’s absolutely nothing improper about backdating a resolution or preparing a resolution that refers to an act that took place earlier,”

the gallery went silent—not from agreement, but disbelief. According to DeFord, time itself is now discretionary, and fabricated paperwork is a legitimate instrument of law.

In any functioning legal system, this would draw a reprimand. In Idaho, it earned a nod.

The Two Resolutions That Weren’t

Consider the pair of “resolutions” the defense offered as proof that a church board had lawfully acted months—or years—earlier. Both bear the letterhead of The Church of God, Apostolic of Idaho, Inc., and both purport to memorialize meetings that never occurred. Both also conspicuously lack the signature of Byron Sanchez, the actual board president at the time of each alleged vote.

The first, dated December 2, 2023, retroactively “appointed” a new trustee, Dorothy Ogren, and then purported to “ratify all corporate activities entered into… over the past year.” Sanchez is listed as “Present/did not sign.”

The second, dated March 9, 2025, claims to have changed the church’s name and to have “ratified” every prior action, again with Sanchez shown as “Present/did not sign.”

In reality, no such meetings took place, and the supposed resolutions were drafted by those seeking to remove Sanchez after the fact. To call these documents “backdated” is generous—they are post-fabricated.

What the Law Actually Says

For anyone unfamiliar with legal ethics, here is the unambiguous rule:

- ABA Model Rule 8.4(c):

“It is professional misconduct for a lawyer to engage in conduct involving dishonesty, fraud, deceit, or misrepresentation.” - Professor Stephen Gillers, NYU: “A lawyer who knowingly creates or endorses a document that misstates the date of its execution commits fraud. The date on a document is a statement of fact. Backdating is permissible only to memorialize an act that truly occurred earlier and is clearly disclosed as such.”

- Professor Geoffrey Hazard, Yale: “Backdating is inherently deceptive unless the document or its transmittal discloses the true chronology. Otherwise, it is tantamount to falsifying evidence.”

- Restatement (Third) of the Law Governing Lawyers § 98, comment f:

“A lawyer may not participate in creating or using a document that is false as to the date or circumstances of its execution.”

In plain English: if the date isn’t true, the document is false.

Courts From Everywhere Else Agree

Federal and state precedents leave no wiggle room.

- United States v. Strohm, 671 F.3d 1173 (10th Cir. 2011):

Backdating corporate minutes to invent earlier approvals was “a deliberate falsification of records.” - SEC v. Dain Rauscher, Inc., 254 F.3d 852 (9th Cir. 2001):

False timing statements in compliance records constituted securities fraud. - United States v. Rowe, 144 F. Supp. 3d 355 (E.D.N.Y. 2015): “Backdating is legitimate only if it memorializes a past event and explicitly states the actual execution date. Otherwise, it is falsification.”

- United States v. Simon, 425 F.2d 796 (2d Cir. 1969):

False dating of documents is “false testimony on the face of a page.”

Even Judge Richard Posner, rarely prone to melodrama, noted in U.S. v. Dial (7th Cir. 1985) that

“A backdated document asserts a falsehood about when an act occurred. Such fabrication, if relied upon, can distort the administration of justice.”

Yet in Idaho’s courtroom that day, these same principles were waved away like an annoying fly.

How We Got Here

When Judge Thomas Whitney permitted DeFord’s assertion to stand unchallenged and later treated those unsigned, retroactive resolutions as legitimate exhibits, it signaled a deeper problem: a judiciary desensitized to falsity.

Backdating is not a harmless clerical error. It rewrites the timeline on which property, contracts, and corporate authority depend. A resolution allegedly “passed” by a board that did not meet—and unsigned by its president—is no resolution at all. It’s a forgery with a letterhead.

To accept it as proof of past events is to endorse revisionist accounting of reality. When a court allows that, it ceases to function as a finder of fact and becomes a notary of fiction.

Why This Matters Beyond One Case

The danger of this precedent stretches beyond one congregation or one litigant. If backdated documents can be waved into evidence as genuine:

- A city council could “ratify” a budget it never passed.

- A corporation could “approve” stock options retroactively to capture a market dip.

- A board could “fire” its president months after he was unlawfully removed—and claim it happened first.

Contracts, titles, and elections all depend on the simple integrity of dates. When courts abandon that anchor, the entire legal system drifts into make-believe.

The National Standard vs. The Idaho Exception

Every jurisdiction that has considered backdating has treated it as potential fraud. Idaho now appears to be the outlier—the one state where the calendar itself is negotiable.

DeFord’s claim that “there’s absolutely nothing improper about backdating a resolution” would draw laughter in a first-year law seminar. In Idaho’s courts, it earned him judicial indulgence. The rest of the country treats false documentation as evidence tampering; Idaho treats it as “creative record-keeping.”

Ethical Fallout

Even if one assumes DeFord sincerely meant “memorializing a prior act,” the documents themselves refute that excuse. They do not disclose later creation. They state definitively that meetings occurred on December 2, 2023, and March 9, 2025—events that never happened—and list a president “present/did not sign.” That final notation is a confession: the individual whose signature would have validated the act refused to sign because the act did not exist.

Under ordinary corporate-law standards, that omission invalidates the resolution. Under Idaho’s newfound temporal relativism, it apparently “ratifies” itself.

A Pattern of Denial and Deference

This episode fits neatly within Idaho’s broader institutional malaise. The Center for Public Integrity assigns Idaho a D-grade for state integrity, and the Better Government Association ranks it near the bottom for transparency and ethics enforcement. Perhaps that explains why a judge could hear an attorney proclaim the lawfulness of backdated evidence and respond with silence. In a state allergic to oversight, fantasy paperwork thrives.

Conclusion: The Land Where Facts Are Optional

In Idaho’s courtrooms, truth seems negotiable, chronology malleable, and signatures optional. Where most states measure justice in evidence, Idaho measures it in audacity.

If Mr. DeFord’s pronouncement and Judge Whitney’s acceptance of those unsigned, backdated resolutions stand as precedent, Idaho has achieved something extraordinary: it has discovered judicial time travel. Who needs honesty when a Word-template and a friendly bench can rewrite history?

Until Idaho’s legal community re-embraces the simple proposition that a date represents reality, every document filed in its courts carries an invisible disclaimer:

“Signed yesterday, dated last year, and certified by the magic of Idaho law.”

(Sources: Official Hearing Transcript, p. 43; Resolutions of Board of Trustees, Dec 2 2023 and Mar 9 2025Backdated Resolution2Backdated Resolution; ABA Model Rules of Professional Conduct 8.4(c); Restatement (Third) § 98 f; United States v. Strohm (10th Cir. 2011); SEC v. Dain Rauscher (9th Cir. 2001); United States v. Rowe (E.D.N.Y. 2015); United States v. Simon (2d Cir. 1969); U.S. v. Dial (7th Cir. 1985); Professor Stephen Gillers, NYU; Professor Geoffrey Hazard, Yale.)

There isn’t a board on the planet that doesn’t email out minutes, resolutions and officer changes the day they happen. The fact that no one has any records that any of those events happened is probably a good indication that they didn’t. Only in Idaho.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I knew that I should have gotten that extended warranty on my car 5 years ago. Here let me back date that….voila! Time to get my transmission fixed!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I get that a sleaze bag lawyer will say anything to help his client- but a judge approving this crap? I hope they are appealing this.

LikeLiked by 1 person