Especially in Idaho.

Reliability matters more than convenience.

Most people understand this instinctively. They will pay significantly more for a product—not because it has more features, or because it looks better, but because it works when it has to. The cost of failure often outweighs the benefit of convenience. A mechanic buys professional-grade tools not because they are flashy, but because a cheap wrench that snaps under torque can cost him a job, a customer, or a finger. A contractor buys a dependable truck not because it is comfortable, but because a breakdown on the way to a job site can mean lost contracts and lost income.

Airlines know this. Hospitals know this. Engineers know this. Reliability is worth paying for because failure is expensive.

The same logic applies to legal proceedings—except the cost of failure is not inconvenience or delay. It is the loss of property, rights, livelihood, and sometimes a lifetime of work.

Yet in Idaho, litigants are increasingly encouraged—or effectively forced—to rely on remote court hearings, even though the consequences of technical failure can be catastrophic.

Imagine an employer who proudly announces a new work-from-home policy. You can work remotely five days a week. No commute. No office politics. Total convenience. But there is one condition. If your internet connection drops—even once—you are instantly fired. Your pension is liquidated. Your stock options are forfeited. No appeal. No explanation. No second chance.

No rational employee would accept that arrangement. Whatever marginal benefit remote work provides is obliterated by the risk of total loss. Convenience becomes irrelevant when the downside is absolute.

Now apply that same logic to court proceedings.

Remote hearings are marketed as modern, accessible, and efficient. For routine matters, they appear harmless. No travel. No courthouse parking. No waiting in crowded hallways. But courts are not customer service desks. They are institutions that adjudicate rights. When a remote system fails, the loss is not a missed meeting—it can be a final judgment.

That is not theoretical. It happened in Ada County Magistrate Court, Case No. CV01-25-17058, before Judge Kyle Schou.

What a Status Conference Is Supposed to Be

A status conference is one of the most routine, informal events in civil litigation. It is not a trial. It is not an evidentiary hearing. It is not designed to resolve disputed facts or terminate cases.

Its purpose is administrative:

- to assess where the case stands,

- to address pending motions,

- to manage scheduling and procedure.

Litigants reasonably understand a status conference to be low-risk. No testimony. No witnesses. No rulings on the merits. In short, a safe setting in which to use remote technology.

That assumption would prove disastrous.

The January 7 Remote Hearing before Judge Kyle Schou

Gary Ogren, age 77, was the respondent in a divorce proceeding. He appeared pro se, without counsel. He had actively participated in the case: filing an answer, filing motions, submitting declarations, and responding to objections. The docket reflects sustained engagement, not neglect.

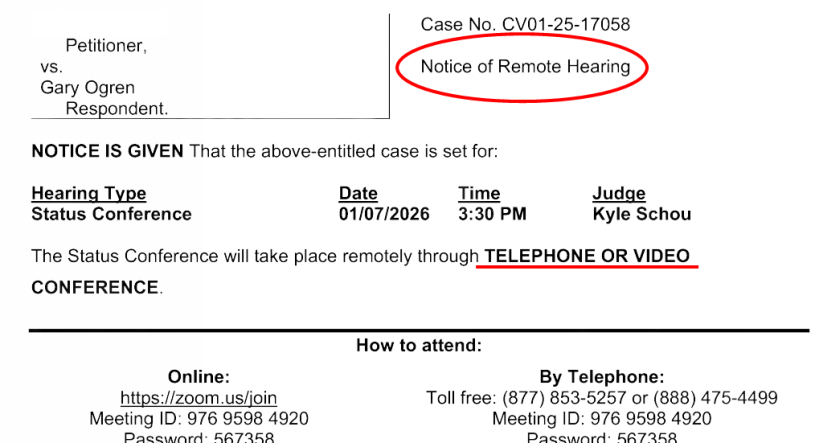

A remote status conference was scheduled for January 7, 2026, at 3:30 p.m., to be conducted by Zoom. Notice was provided by the court.

Gary prepared for the hearing as instructed.

Between approximately 3:15 p.m. and 5:00 p.m., Gary attempted to connect approximately ten times by phone. Each attempt resulted in the same pattern: the call would connect briefly, place him on hold, and then disconnect. He continued trying.

This was not refusal. This was not neglect. This was not willful nonappearance.

It was a technical failure. The court minutes for January 7 reflect only one thing: “Respondent did not appear.”

There is no mention of:

- attempted connections,

- technical difficulties,

- dropped calls,

- or access failures.

In a physical courtroom, an empty chair invites inquiry. In a remote hearing, silence is treated as surrender.

The Consequences

The consequences were immediate and severe.

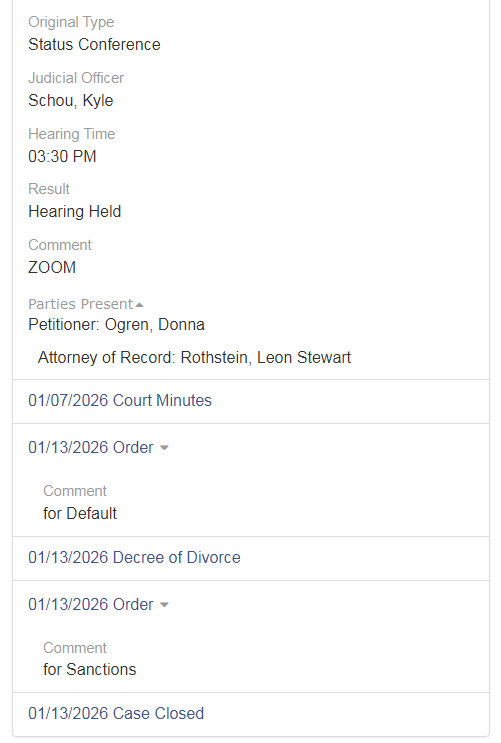

On January 13, 2026, Judge Kyle Schou entered:

- an Order for Default,

- an Order for Sanctions,

- a Judgment and Decree of Divorce,

- and closed the case entirely. CaseCV01-25-17058

The petitioner, Donna Ogren, represented by Leon Stewart Rothstein, received everything.

Gary Ogren lost:

- his home

- his vehicles

- most all of his personal effects

- family heirlooms

- all savings

The consequences were immediate and severe. She got everything!

All of this occurred without an evidentiary hearing, without findings of willfulness, and without addressing the technical failure that prevented his appearance. A routine status conference became a procedural guillotine.

Proportionality and Due Process

Courts possess sanction authority, but that authority is not unlimited. Striking pleadings, entering default, and terminating a case are among the most extreme sanctions available. They are intended for willful disobedience, bad faith, or repeated abuse of process.

Here, the record shows the opposite:

- Gary responded to filings.

- Gary filed motions.

- Gary appeared when able.

- Gary attempted to appear on January 7.

When Judge Kyle Schou sanctioned a litigant into default because of one failed remote connection removes the distinction between misconduct and malfunction.

That distinction is the heart of due process.

The Unique Danger of Remote Hearings

Remote hearings shift all technical risk onto the litigant. The court controls none of the variables:

- phone networks,

- internet stability,

- software glitches,

- system load,

- audio routing,

- or platform outages.

Yet when failure occurs, the record does not say “system failure.” It says “failure to appear.”

This is not a neutral shift. It is a structural hazard.

Remote hearings disproportionately endanger:

- elderly litigants,

- pro se parties,

- disabled individuals,

- those without counsel monitoring the connection,

- and anyone without redundant technology.

In a system where silence equals forfeiture, reliability becomes paramount—and remote systems are not reliable.

Remote hearings offer convenience. But when the risk is total loss, convenience becomes irrational. No one would sign a contract where a single technical failure voids all rights. No one would board an aircraft if a brief radar outage meant the plane would crash. No one would accept a bank that liquidates accounts during a server hiccup.

Yet Idaho litigants are increasingly asked to accept exactly that risk. This is not just about one case. If a litigant can lose everything at a status conference because a phone line fails, then:

- custody cases are at risk,

- property disputes are at risk,

- probate matters are at risk,

- protective-order proceedings are at risk.

The system treats remote access as equivalent to physical presence—without accounting for the radically different failure modes. That is not modernization. It is abdication.

Remote hearings are not inherently evil. But they are inherently unreliable.

In Idaho, the cost of that unreliability can be absolute: default judgment, sanctions, and permanent loss of rights—without testimony, evidence, or intent.

The lesson is stark but necessary:

No matter how convenient a remote hearing appears, if you cannot afford to lose your case completely, do not rely on it.

One dropped call can cost you everything you have worked for. Now whether the blame can be placed upon one bad connection, one crooked attorney or one corrupt judge, the effect is the same. The convenience of a remote hearing isn’t worth the risk. And in the State of Idaho, that is not speculation. It is now part of the record.

I thought bull riding was risky. Turns out the real danger is trusting Idaho courts to keep a phone line connected.

LikeLike